Those who were fortunate to be part of the inaugural Robben Island Museum Memorial Run 10km not only helped to both commemorate and make history, but also came back with a unique running experience that many are still talking about, weeks after the race. No wonder many are already asking about 2024 entries! – By Sean Falconer

Tag: History

‹ BackWhere The Two Oceans Meet

Venter’s Visionary Race

The Totalsports Two Oceans Marathon was first run in 1970, and there is an interesting story behind that first edition of what is now one of the biggest and most internationally renowned races in South Africa. – By Sean Falconer

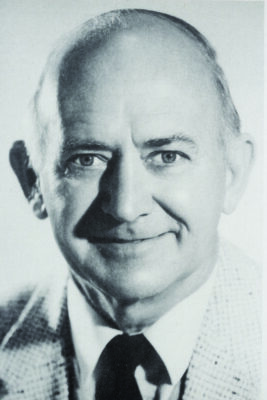

The fledgling idea for the Two Oceans Marathon was born in the late 1960s when former Durban-based runner Dave Venter was transferred to Cape Town by his then employers, BP Southern Africa. To his great disappointment, Venter found that running in the Cape was very much behind Durban, where the 90km Comrades Marathon had been on the calendar since 1921. He had been a keen member of Savages Athletic Club and had run his first Comrades in 1967, just a year after starting to run at age 36, but in the Cape in 1968, there were only a handful of marathons to choose from and no ultra-marathons.

Venter ran the Stellenbosch Marathon, which only had about 20 entrants, and then had to wait several months for the Western Province Marathon in Bellville, which attracted a mere five entrants. Shortly after this, he took two months’ leave and returned to Natal to run his second Comrades, as well as the Bergville/Ladysmith Ultra. He was actually playing with the idea of asking BP for a transfer back to Natal, but after discussing it with former clubmate Gerry Treloar of Savages, he decided to give the Cape another chance. This after Treloar said, “Now that you’re there, why don’t you try and improve long-distance running in Cape Town?”

That convinced Venter to try to start an ultra with a similar distance to the Bergville/Ladysmith, around 35 miles, as he reasoned that runners in Cape Town planning to run the Comrades would enter it as a training run. However, when he took the idea to Celtic Harriers, the club committee said they didn’t feel there was any need for such a race in Cape Town.

The Western Province Amateur Athletic Association (WPAAA) also turned the idea down, but help was at hand. Through Celtic Harriers secretary Harold Berman, Dave was introduced to The Argus sports reporter Bryan Grieve, who lent his public support to the idea. At the same time, Stewart Banner was elected chairman of the WPAAA, and he too gave a favourable response, so Venter decided to try again. He went back to Celtic Harriers and said if the club would give him its backing, he would take care of all arrangements and ensure the club was not involved in any way.

Convincing the Doubters

With that agreement in place, Venter attended a WPAAA committee meeting in late 1969, and after a heated debate, he was finally given permission to hold the race on 2 May 1970 – just one week after the Peninsula Marathon, in spite of the small number of long distance races on the calendar at that time. Interestingly, the most outspoken critic of the idea was journalist and statistician Harry Beinart, who said he did not see the point of a 35-mile event!

Meanwhile, the WPAAA said the race should take place in May, at the end of the track and field season, so as not to impact other events on the calendar, and added one further strict condition: The race should not interfere with the cross country event scheduled for that afternoon – and Celtic Harriers echoed this condition!

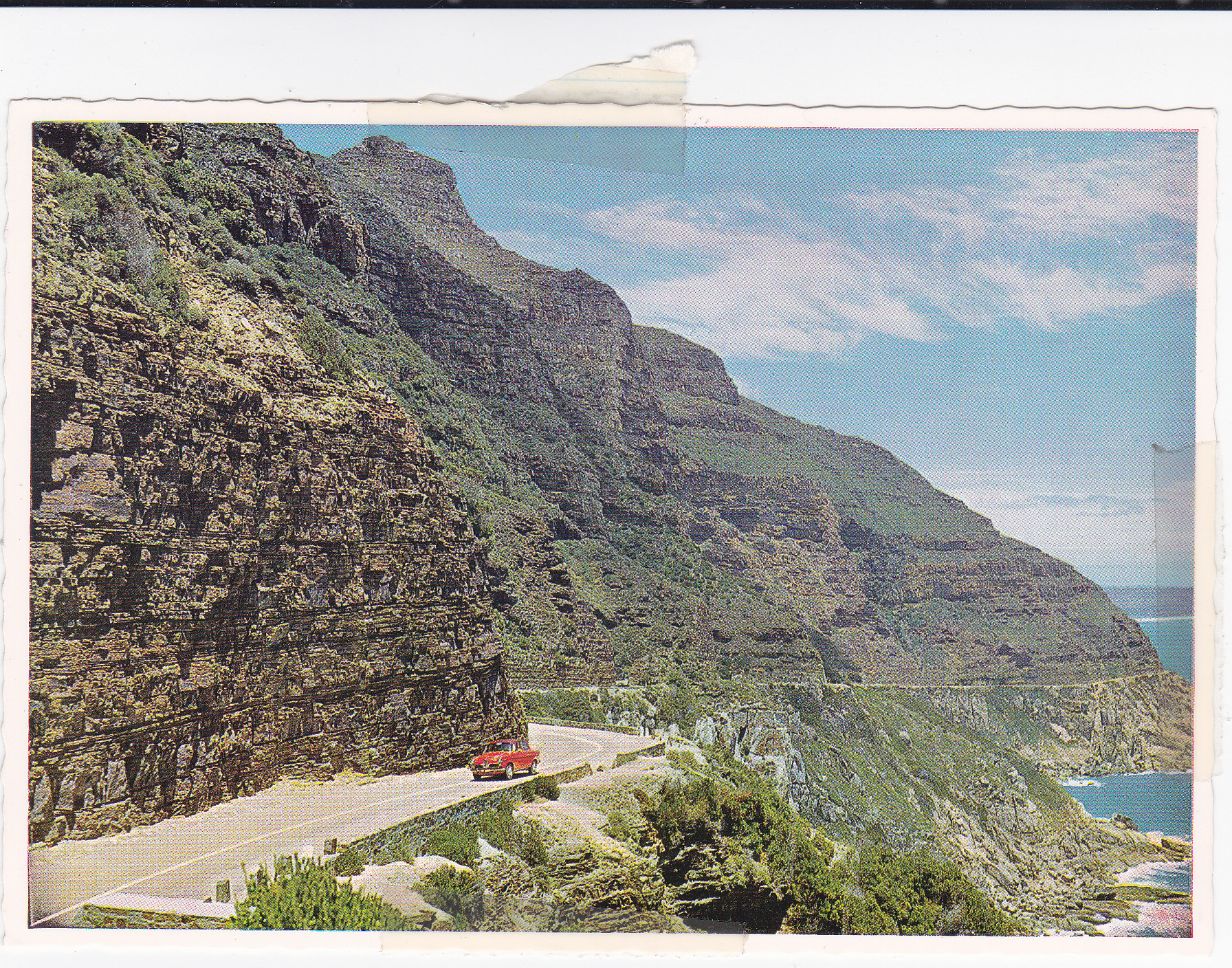

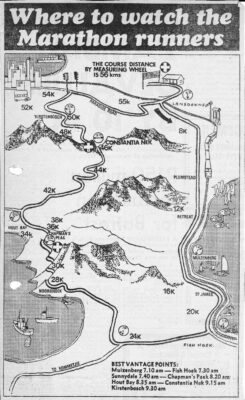

With that hurdle out the way, Venter had an easy decision to make. His favourite training route ran through Muizenberg, Fish Hoek and Noordhoek, over Chapman’s Peak Drive, through Hout Bay, up Constantia Nek Drive and Rhodes Drive, down past Kirstenbosch, offering an incredibly scenic route measuring the approximate distance he was looking for, so the choice of route was simple. He also found a suitable venue for the start and finish by asking BP if he could use their Impala Park grounds in Newlands, and BP donated a floating trophy for the winner.

Getting to the Start Line

The race flyer for the first Celtic 35 Mile Road Race duly went out, with extra emphasis on this being a perfect training run for those planning to run the Comrades. The entry fee was set at 50 cents, with entries closing on 29 April. Runners would need to supply their own seconds to compliment the sponges and drinks available at the 10, 20 and 30-mile markers, where timekeepers would be stationed to record each runner’s progress. The top three finishers would receive prizes, thanks to Venter donating some of the prizes he’d won in Durban, and he also contributed another R6 in order to buy a few extra awards.

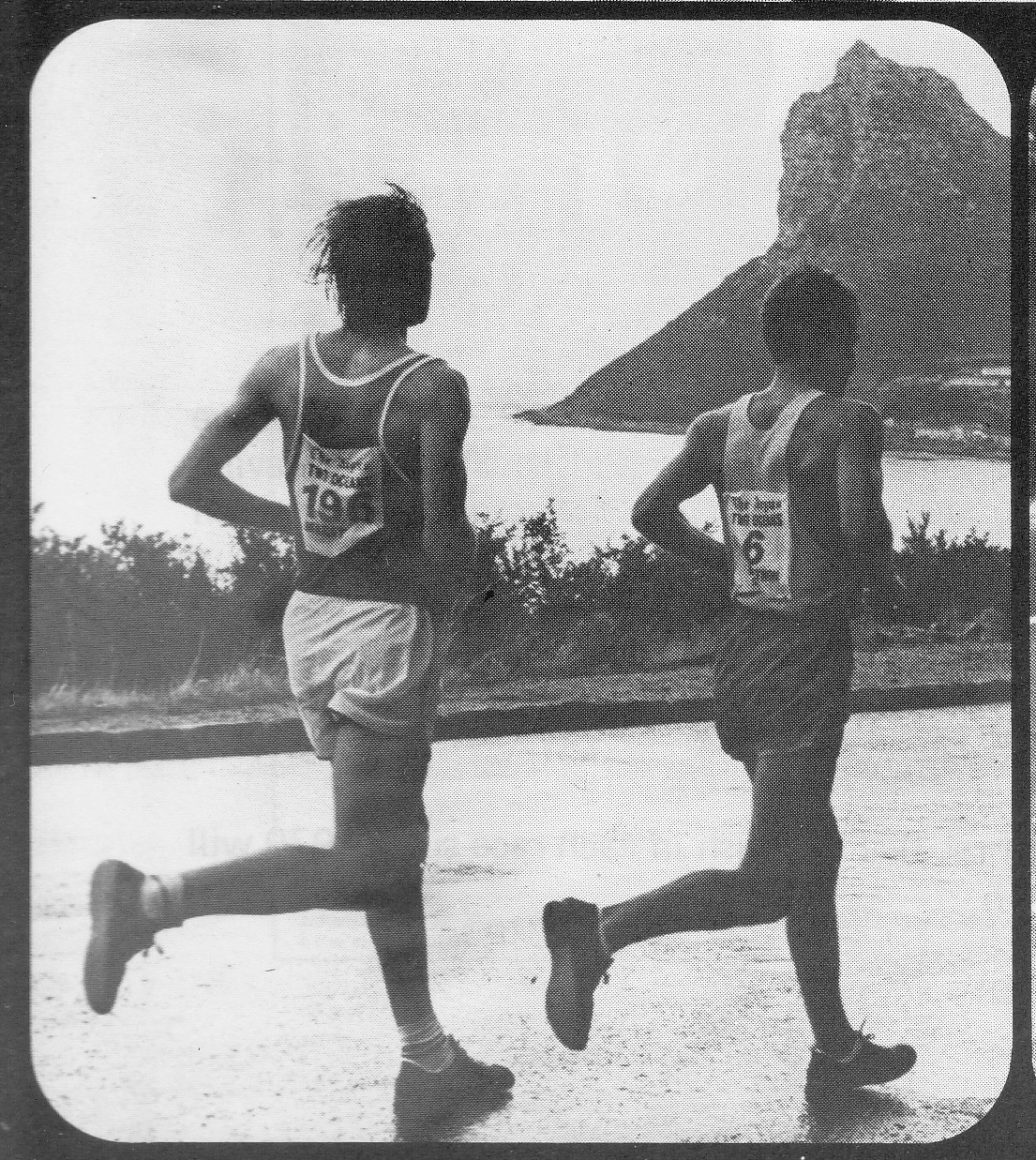

Race day arrived, with a small but intrepid group of 24 runners lining up on a wet, blustery morning in Newlands. Dirkie Steyn would go on to win that first edition of the race, in 3:55:50 – and remarkably, he ran the entire race barefoot! It was the start of 50-plus years of incredible running around the Cape Peninsula, and out of that first, small race was to grow one of the biggest running events on the South African calendar.